A useful framework for considering one investment is to compare it with another, you can then do analysis to decide if you prefer one to the other. This is of course relative value and if the benchmark asset is government debt, this is a solid place to start.

The “Fed Model”

The “Fed Model” is that the stock market yield is related to the yield on long-term government bonds. Like so many models, it has fallen into disrepute seems to come more from its misuse over the years as opposed to its intrinsic failings.

Expected Returns for Equities and Bonds

A way to start thinking about this model is to start with the expected returns on the two investments, equities and bonds. Consideration of the spread of returns and the distribution around the expected return can come later.

Bonds

Expected return for US government bonds in nominal terms is as easy as it gets – yield to maturity.

I will ignore the remote possibility of a default on the debt.

Equities

Expected returns for equities is harder; there is a choice of possible yields, with none necessarily equating to the eventual return.

- Dividend yield

Problematic given that dividend policy is a management decision. Microsoft’s decision not to issue dividends was not a good indicator of its total return. - Earnings yield

More sensible i.e. E/P (or just PE ratio inverted). - Earnings yield + Inflation

Considering we are using historical earnings, to get a future value we could add an inflation component given that earnings would be expected to rise along with inflation, in the long run.

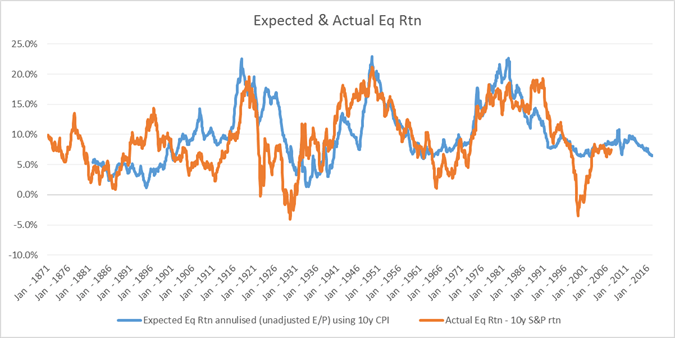

Testing the expected returns model for Equities

Back-testing expected returns to 10 year actual returns, the US equity market shows surprisingly good results, especially post WW2. This makes intuitive sense as one would expect that buying equities with a lower PE or when inflation is higher would produce better returns. But the strength of the relationship is eye-catching, implying that current earnings do on average provide a good guide to expected equity total returns.

If you come from a purely “efficient markets” view of the world, this may seem blindingly obvious with equity value as simply the present value of the earnings stream. But bear in mind that earnings yield (E/P) is not a yield in the same way that bonds have a yield, unless you make an argument where the word “assume” occurs very frequently.

Expected Returns for Equities versus Bonds

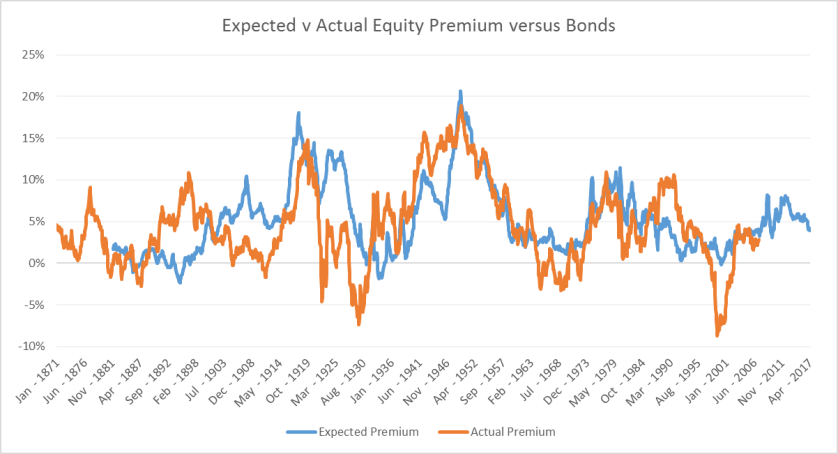

Given that we are happy with our model of expected returns for both equities and bonds, we can move on to comparing one versus the other.

The model for expected return of equities over bonds would look like

We can use data from end 2016 to get actual numbers

This difference/expected return is often called an equity risk premium (ERP).

We can now back-test its use in predicting if the equity market will actually outperform the bond market. Chart below again shows pretty decent relationship – but can we say how good?

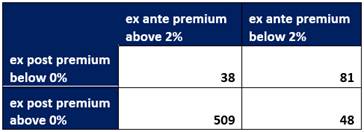

Given the nature of the data we should not perform a regression, and instead here is a truth table for the data back to 1950.

With ex ante premium (i.e. model) above 2%, then equities outperform bonds 93% of the time.

With it below 2%, then equities only outperform 37% of the time. That is a pretty solid result.

Summary

This investigation that equities look cheaper than bonds. If this is the only model you use then the clear imperative is to buy equities now. Before I make my mind up, I want to think about fixed income valuation next.