“That’s the trouble with hope. It’s hard to resist.” The Doctor to Missy

Desire is everywhere

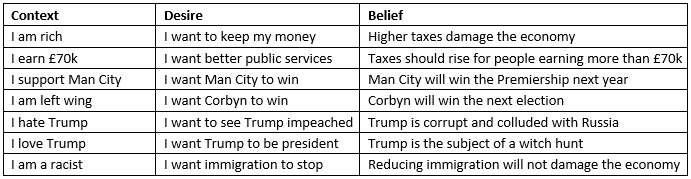

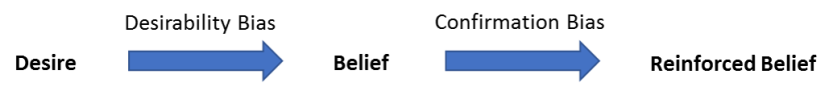

I introduced the link between desire and beliefs in my last post. As humans, this is how our brains are wired. A way to think about the human thought process is this:

Desire is dangerous and hard to resist

Recently, we have witnessed desires replacing beliefs as the central element of the political discourse. The recent Brexit campaign was perhaps the ultimate triumph, as the debate centred on deep seated desires “Do you want to leave the EU?”

The Leave campaign focused on stirring powerful emotions, whereas the Remain campaign had no emotional resonance, relying upon things no-one cares about such as economics and facts! The level of debate was astonishingly poor because it was not really a debate at all. It was an emotional primal scream and clear evidence that desire leaves beliefs trailing in the dust.

How to combat desire

One of the ways that I combat the power of desire is to try to become consciously aware of it. If I have a belief, I try to work out if it matches with my desires. If so, I may be prone to desirability bias and note it as something to be wary, of as we mentioned in the previous piece. This is especially important for doing fundamental analysis for trading, where is can easily influence my decision-making process.

Let’s use some recent examples:

- I remind myself to tone down the potential importance of anti-Trump developments

I read Fox News and the NY Times,

I watch John Oliver and …. OK I cannot watch Fox and Friends

- I read the Telegraph every day during the Brexit campaign

If my belief does not match any desire I have then I note that while I might still be wrong it is unlikely this type of error. For example

- I do not want the UK economy to be wrecked, but I think that Brexit might do it.

- I have no particular love for the EU, but I think Brexit is a disaster.

This means that my belief that Brexit is a disaster likely comes from my analysis rather than by analysis being driven by my desires. I still have to consider other ways in which I might be wrong but eliminating the really disastrous one is the most important.

- I would prefer that the US equity market were very cheap

So my analysis that it is expensive is disappointing but likely not driven by a desire.

Desire is a particular problem for investors

Investors are particularly vulnerable to these problems of desires influencing beliefs.

Given that our beliefs on the market require frequent updating based upon new information, any cognitive error in processing such information can often lead to poor decisions and emotion taking over. The related but more important problem is our desires as investors are not independent from the act of investing. The very act of making an investment changes our desires.

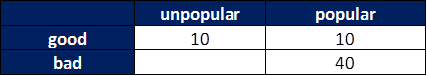

Let’s use an example is have used many times in the past 25 years.

Imagine I take you to a racetrack.

There is a race coming up and I ask you which horse you think will win.

You do not know much about the horses and so have no view independent of the odds you can see posted.

I give you £10k and say you have to put it on a horse that is 5-1. If you win you get to keep the winnings.

Now you care.

You are going to have £50k in your pocket if your horse comes in and nothing if it loses.

What do you think happens during the race? I bet you get pretty excited. When your horse is edging in front with 2 furlongs to go you are jumping up and down with excitement and are convinced you are going to be rich.

I offer to pay you £10k now to cancel the bet. You look at me as though I am crazy or trying to steal from you as you are about to win £50k. you are very confident.

Your horse tires and comes in sixth. Your horse is a well-known front-runner who tires badly. But you did not seek out that information and are shocked and deflated.

But it was pretty exciting and you can’t wait to do it again.

Conclusion

If you do not combat it what you want to believe will have a dominant impact on what you end up believing to be true. If you sit inside your bubble only listening to people you like and respect then you may be falling prey to Desire.