I do a very different analysis of the long-end of the yield curve, compared to the front-end. (Framework for valuing fixed income – Front end) Mathematically, you could take the same approach and bootstrap the curve from a complete set of forecasts of short-term rates for the next 30 years. But this seems a bit silly and begs the question of how you would get these forecasts anyway.

To simplify the analysis, what we have to work out is what the long-term “equilibrium” rate will be and ignore for now how we get there or use the analysis from the front end to build a path.

Simple Hypothesis: Long-Term rates = Nominal GDP

An approach that appeals to me is to look for a link between long term interest rates and long term nominal GDP. I think of it as a “Wicksellian” natural rate which the market will tend to revert to i.e. If interest rates are consistently far away from the growth rate of nominal GDP then there would be a persistent drag or stimulus to growth which would not be sustainable. You can get to a similar idea from several different economic frameworks.

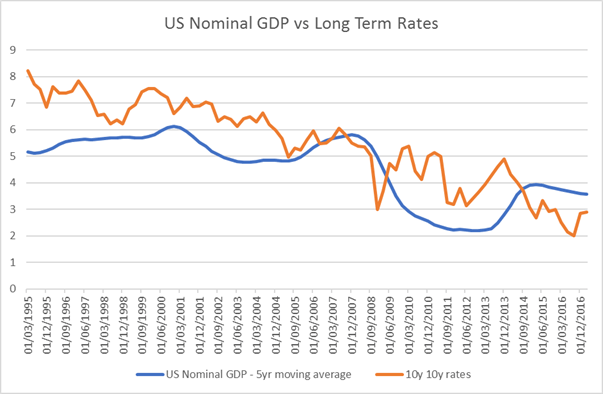

If we look at the data then, the hypothesis looks reasonable. Below is the 10-year average of nominal GDP growth alongside the 10y10y interest rate for the US. The 10y10y rate is the rate you can calculate as what the market implies the 10y interest rate to be in 10 years’ time.

Before the early 2000s, interest rates were consistently a little higher than GDP. Academics were happy with this and explained it in terms of some type of premium which bond owners would demand to own bonds. They were then confused in the early 2000s by the “conundrum” that long term yields dipped, explaining it either by Chinese ownership of Treasuries or a global “savings glut” which was forcing down yields.

Outlook for Nominal GDP

Current yields do not look very remarkable to me, but they are only correct if you think that nominal GDP will remain as low as for the past decade. The most prominent argument that we should expect this to continue comes from Larry Summers and his promotion of the idea of “Secular Stagnation” – http://larrysummers.com/2016/02/17/the-age-of-secular-stagnation/

I find these arguments a little hard to engage with as we must recognise how utterly useless long-term forecasts of anything generally are. I should admit that I am not a big fan of anything which looks like a restatement of the savings glut theory to me, but I do not want to engage here in an academic debate. As a more practical question, I think that the burden of proof is on ideas such as Secular Stagnation and the “New Normal” that the world will need permanently far lower rates than it has in the past. Arguing that nominal GDP will be lower, due to slower population growth, demographics and potentially lower productivity is easy. Explaining why it is 3% lower is not so easy.

My view is that this economic cycle does not require new theories to explain it. A financial crisis results in a very deep recession and leaves scars which mean the recovery is slower than many expect. These hangovers from the financial crisis are what Yellen refers to as “headwinds” which are slowing down the economy. Risk aversion among consumers and businesses after such a bad recession is only to be expected and the impairment of the credit channel after such a disruption is also understandable. But there is no reason to think that these headwinds are permanent. They can abate and we can return to a world similar to the one before, both in terms of the level of nominal GDP and also the relationship between interest rates and growth. The financial crisis has been traumatic, especially for countries like the US and the UK, that have not seen one like this recently. However, the history of financial crises is that they are worse than people think, but they are not permanent.

Are we renormalizing?

Unemployment fell slowly but is now down to 4.5%. wages have been sluggish but are now picking up.

If I draw the first chart again but this time use a 5yr rather than 10yr moving average then perhaps I can argue the market is reacting too slowly. Nominal GDP has been rising recently and with rising wages and inflation can easily be seen to be likely to continue to do so. If that is true then market rates are too low.

Why are long term rates still so low?

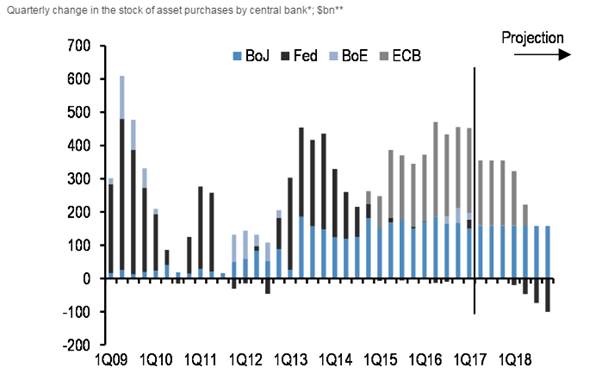

The idea that long term rates are too low is hardly new. After all this was the whole point of QE!! The central banks buy huge amounts of long term debt to drive up bond prices and yields down. This helps to stimulate the economy and boost other asset classes which look relatively cheaper to bond markets, and so drives reallocation flows.

As I mentioned in this post (https://appliedmacro.com/2017/05/01/government-debt-framework-uk-follow-up/), we are living in a new era of financial repression. Therefore, I really do not need any grand theory from the supply side of the economy to explain low rates. I just look at the huge boost in demand for bonds from the central banks.

Is there a catalyst for change?

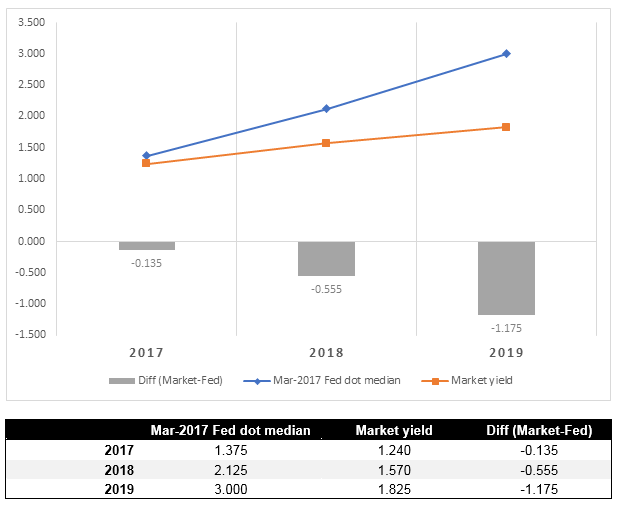

- One potential catalyst would be from the front end. If the Fed hikes rates faster than the market expects, then this can cause a shock to ripple down the whole curve. We saw an extreme version of this in 1994.

- If wages start to accelerate then the Fed, economists and market participants would have to radically reassess their assumptions about the inflation outlook and the appropriate level of rates. If you are very confident this cannot happen, you have more faith in our understanding of this type of macro variable than I have.

- Even without any fundamental driver we may see a repricing simply from a change in the supply and demand dynamics of the bond market.

QE buying has been high for the past few years but it is finally slowing down. This may be the catalyst for a repricing of bonds.

Conclusion

A simple and yet historically useful framework for considering long term rates is to use nominal GDP. In recent years, we have seen the combination of a major downshift in long term expectations for both nominal GDP and the level of rates relative to nominal GDP. While many arguments justifying this change as permanent have some merit, I think that they are more temporary then current market pricing implies. Which means that I do not think that bond markets are cheap. In fact, I think they are wildly expensive.