I will again use the bestselling undergraduate textbook “Macroeconomics” by Greg Mankiw as the source for this story.

How does money get created?

In the beginning, there were bank reserves……

- The Central Bank determine Bank Reserves – this is the money that the banks have on deposit with the Central Bank

- Banks, holding these reserves, then lend them out to customers, who then either put that money on deposit themselves or transfer the money to someone else who does. The mountain of customer deposits is generally many times larger than bank reserves. This is known as the “reserve-deposit ratio, rr”.

It is an “exogenous variable” in other words “the model takes as given”. - There is also the currency in circulation which the central bank also determines.

This is known as the “currency-deposit ratio, cr”. It is also an “exogenous variable”. - Combining these via “money multiplier”, gives you the Money Supply.

In this way, the Central Bank determines the level of reserves, and thus controls the money supply in a predictable way.

From bank reserves to money supply to inflation……

The next stage in this story is the “Quantity Theory of Money” which “remains the leading explanation for how money affects the economy in the long run.”

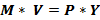

This starts with a key identity or equation:

Add a few assumptions….

P * Y is also nominal GDP, so if we assume that V (the income velocity of money) is constant (or “exogenous”), then a change in M leads to a change in nominal GDP.

Via a separate assumption, the level of output Y is determined by a production function which does not include money, therefore a change in M leads to a change in P i.e. changing the money supply causes inflation.

Economists are taught this key conclusion at university:

“Thus, … the central bank, which controls the money supply, has ultimate control over the rate of inflation.”

Unfortunately, like many Creation Myths none of this is true.

As Mankiw says, this model “is simplified. That is not necessarily a problem.”

I agree, “all models are simplified”. But when causation is the wrong way around, this is a massive problem.

Banking – a personal perspective

When I left university, I became a trader at a bank, spending many years on a money markets desk. It is at the least glamorous end of trading, but I found it fascinating being at the centre of the banking system, funding the bank’s activities, and forming the link between the Central Bank and the markets. What was immediately striking was that bank operations were nothing like the models I had been taught at university.

In the story above, the driving force is the Central Bank adding reserves, causing banks to lend money. The mechanisms described are correct, just in the exact opposite order. The actual sequence goes something like this:

- Customer decides to buy something and uses credit card for the purchase.

- Transaction goes through. i.e. bank lends the customer money for the purchase.

- The money shows up as a credit entry on the shop’s bank account and a debit entry on the credit card.

- The banking system now has a debit and a credit. Banks move the money between them to square their accounts.

- It is important to note that the central bank wasn’t required to do anything in this process.

What if the customer takes out cash? Then the banking system is short of reserves.

This is not a problem as the central bank just adds or takes out reserves on a regular basis to make sure the banking system has exactly as much as it demands.

It is not the case that the Central Bank tells the bank funding desk it has more reserves, who then calls round the rest of the bank to tell them to do some more lending. In simple terms the central bank sets the rate of interest (Fed Funds in the US and the Base Rate in the UK) and then supplies money as demanded. The supply of money is determined completely by the demand for money.

Evidence

Correlation of money supply with inflation

Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz “wrote two treatises on monetary history that documented the sources and effects of changes in the quantity of money over the past century.” What they did was document that money supply and inflation are positively correlated. This is a most obvious prediction from either story of money, and so I have never seen an argument that it supports one over the other. As inflation rises, then more money will be demanded in the economy to facilitate transactions. The central bank accommodates this so we see a direct relationship between money and inflation. This tells us nothing about causation. Friedman’s attempts to show causation by econometric tricks with “long and variable lags” are completely bogus.

Stability of velocity of money

An argument for why one can assume V is a constant, is that historically, over short periods, it has been. Unfortunately, this again is a direct prediction from both stories. If the central bank always supplies as much money as is demanded then there is no reason for velocity to change.

Why did QE not lead to hyperinflation?

According to this monetary theory in the textbooks, the vast increase in reserves caused by Quantitative Easing should have led to an explosion in bank lending and a rapid rise in inflation.

This clearly hasn’t been the case, and in fact, the taught theories really struggle with reality here. They are forced to rely on ad hoc and non-quantitative explanations such as “animal spirits” or a reduction in confidence. Since this “confidence” is not directly predictable or even observable, it requires a leap of faith, equivalent to “magic”.

It’s a wonderful coincidence that a model which predicts a MASSIVE stimulus finds, in reality, an unseen counterbalancing force which is of EXACTLY the same magnitude. But still, I read that MV=PY holds and the miraculous drop in V to exactly offset the rise in M, was a bizarre coincidence and that once the velocity of money rises back to “normal”, inflation will come.

There is a much simpler explanation. The amount of loans created by banks was never constrained by reserves and so increasing reserves has no effect on the behaviour of banks or their clients.

What do central bankers say they are doing?

Central bankers involved in monetary policy and the oversight of the banking system must understand how banking works. What do they say is going on?

They agree with my model and say that “the reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks” and describe the model that is taught as “some popular misconceptions”. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

Conclusion

Money is simply not exogenous and does not cause inflation.

Amongst practitioners, including bankers and central bankers, this is obviously well understood. Bagehot famously described it perfectly in 1873. What is striking is the contrast to academic economists who persist with a very different mythical version of banking and continue to educate our bright, young minds with a story of pure fantasy. So why do they do it? I will speculate on that in the next post.