I used this phrase in a post two weeks ago (Models – How do computers play chess?), and in causing some debate, has made me realise how it has both subtle and important differences in meanings. This has implications for how we approach problems and links to some of the root causes of mutual incomprehension that I often come across.

Some of the different meanings:

1). General usage

It is the same as “first approximation” or a “ball park estimate” and used interchangeably. It is an educated guess with a few assumptions and likely a simple model. I think this is the most common usage. It tells you nothing about the nature of the model as this will vary by context.

2). Engineering/physics

Often used as an indication of level of accuracy, like significant figures, and this accuracy improves with higher orders of approximation. For example, if estimating the number of residents of a town the answers could be:

1st order approximation / 1 sf 40,000

2nd order approximation / 2s.f. 37,000

etc.

3). Mathematics

1st order often refers to linearity. For example, a Taylor series of a function of the form:

1st order approximation a + bx (also called a linear approximation)

2nd order approximation a + bx + cx^2 (also called quadratic)

Order also exists in statistics, with arithmetic mean and variance known as the first and second order statistics of a sample. Skew and kurtosis are third and fourth order and can be thought of as shape parameters telling how far from the normal distribution you are.

4). Financial derivatives pricing

For option pricing, it refers to the order of differentiation, so is helpful when thinking about sensitivities in the change in price:

1st order approximation Delta (1st derivative of price with respect to underling price) 2nd order approximation Gamma (2nd derivative of price)

For bond pricing, second order approximation is also called convexity adjustment which again is used to help understand the non-linearity of bond prices.

5). It can refer to the number and importance of the variables in a model.

A first order approximation may only deal with primary drivers. A second order model would include secondary drivers used to refine the estimate.

For example, a first order approximation of the time taken for a ball to drop would be to use Newton’s second law, F= ma. A second order approximation might include some appreciation of wind resistance.

The meanings may not align

These definitions might appear to be much the same thing. You can easily argue that a simple linear model using only the most important drivers will produce a decent ball-park estimate to one significant figure.

But this apparent similarity of definition means that a common trap is to not notice when they are different.

- A first order approximation can be quadratic

To estimate the height of a cannon ball after firing we need to draw a parabola not a straight line. Often the non-linearity is so important that any linear model is awful.

(see How Not to be Wrong: The hidden Maths of Everyday Life by Jordan Ellenberg).

- Making estimates more “accurate”, using higher power terms may make the model worse

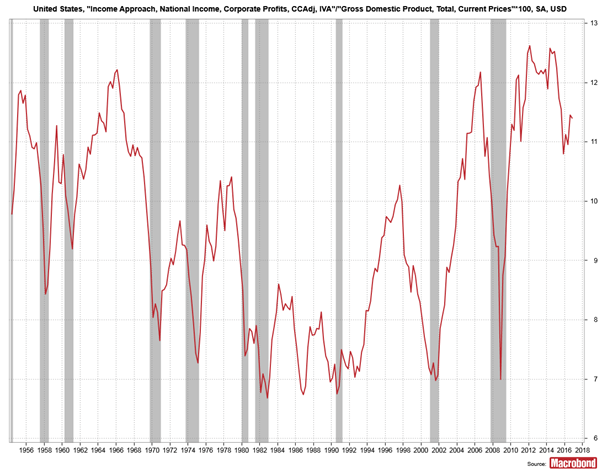

In maths or physics textbooks, this approach always works out given that you already know the mathematical function or have an underlying relative which is stable. But in the world of economics and finance it can lead to a huge methodological error, thinking that the better our model fits the data the better the model. I worked with many analysts who have struggled with this and kept producing models with wonderful correlations and R^2. This leads them to think they have a model which “explains” the price action as well as possible. But these models are invariably useless, have no predictive value and need to be “recalibrated” to make them refit new data as it comes in.

- It takes judgement to know which variables to use.

For instance, in the example with dropping an object, Newton’s second law will do an excellent job on a ball bearing from 10m but a pretty poor job on a parachutist. Which drivers will be important in financial markets varies over time and it takes a lot of flexibility to stay open-minded as to potential outcomes.