Skill and chance

A common way to think about games is that they are either games of skill, like tennis, or games of chance, like roulette. But this basic categorisation can lead to some important misunderstandings. A far better way to categorise them is in two dimensions, skill and volatility.

Introducing Skill and Volatility

Games can instead be categorised as having:

- High Skill – where the result is importantly impacted by the relative skill of participants.

- Low Skill or Unskilled – the result will mostly likely be to chance (Random)

We can also categorise them by volatility of outcome:

- High Volatility – The winner and margin of victory of any particular result will be variable and somewhat unpredictable

- Low Volatility – The margin of victory will be similar each time the game is played.

By “game” I’m using a fairly general definition – any competitive activity where you can judge who is the winner and often how easily the win was achieved. Games such a chess and poker, competitive sports such as football and tennis would clearly fall under this definition but similarly so can trading and starting a business.

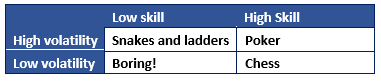

This approach yields a 2 by 2 grid:

Let look at some examples for each quadrant:

Low skill element combined with high volatility

e.g. Snakes and ladders, roulette

Snakes and Ladders is clearly a game of chance with no skill but is surprisingly fun to play with kids. Climbing ladders ahead of the competition or sliding down huge snakes and losing your lead produces a lot of drama and excitement.

Games of no or low skill and high volatility make excellent games for young children. They are also quite common for adults but generally when money is added to the equation as they make popular gambling or casino games.

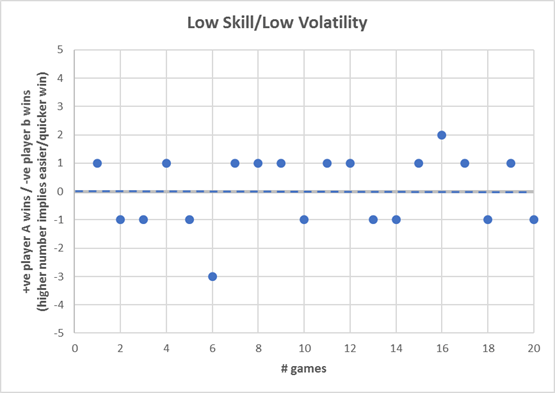

If we consider the distribution of outcomes of 20 matches played between 2 players, it might look something like the scatterplot below:

- X axis is each game played.

- Y axis is the result.

Above zero signifies player A wins, below player B wins. 1 would signify a tight match, 5 would signify a relatively easy victory. In this case, we do not have draws – zero scores.

Low skill element with low volatility

a very boring game!

Snakes and Ladders without any snakes or ladders would be an example of this. The winner is the person who on aggregate throws the higher score when rolling dice. This seems extremely dull and not something that people would do for a purpose or for enjoyment.

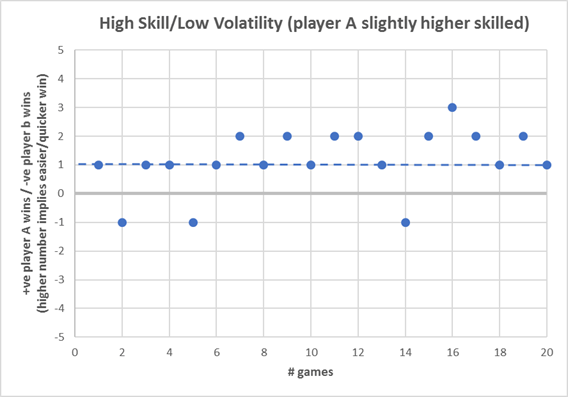

High skill element with low volatility of outcome

e.g. chess, Go

Here the skill element dominates relative to the volatility of the outcome. In this category, we find

chess and Go and sports such as tennis. A significantly better player is almost certain to win and, in that respect, these games often do not work well socially as weaker players have little chance of winning so will not enjoy very much. These are the games I work hard at to become expert and enjoy fierce competition with players of a similar standard.

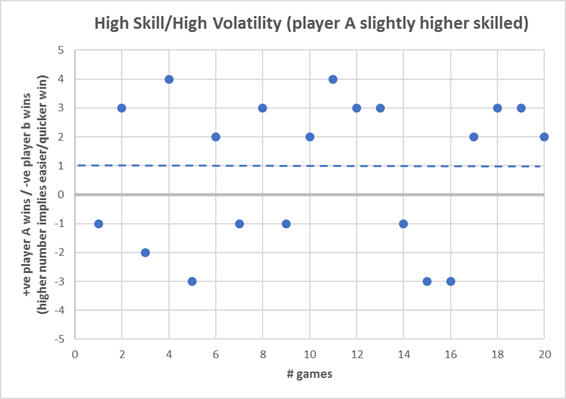

Non-random with high volatility

e.g. pool, poker

This is the category that holds the most socially fun games. The skill element is undeniable but the outcome is uncertain enough that the lesser skilled player still has a chance to win. The uncertainty may even be sufficient that the weaker player may consider themselves the stronger one.

Volatility the key ingredient

People tend to be somewhat aware of the skill level of games. They tend to be less aware of the volatility of the game and why it matters so much.

Pool is a lot more fun to play socially than snooker. Both involve almost the same skills, but pool has much higher volatility. A better snooker player will take virtually every frame; but with a similar difference in skill the weaker player would still win some games of pool.

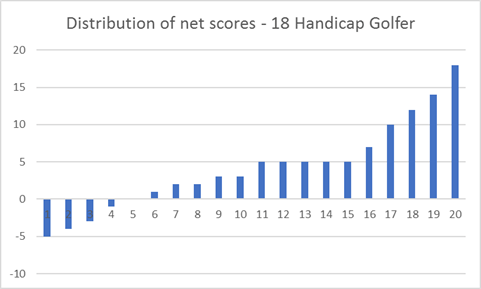

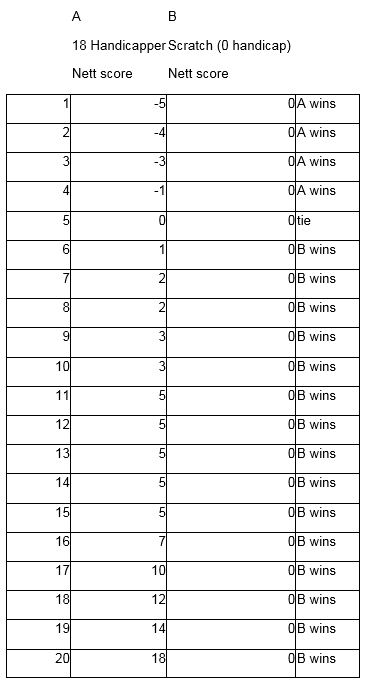

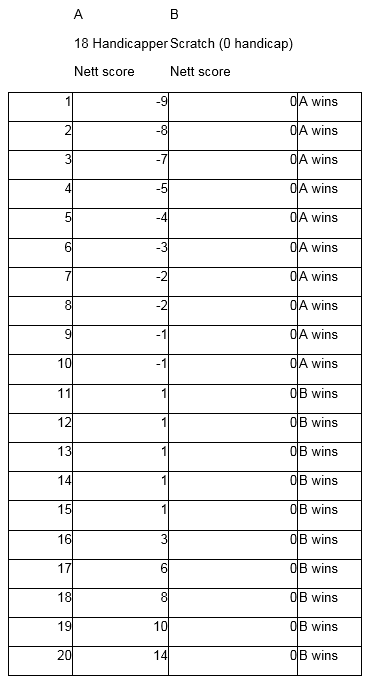

Golf is another game with high volatility and high skill. Even top professional golfers can have a range of 20 shots between their best and worst rounds. On any given occasion, players of slightly different standards can play together uncertain of the outcome, although they know on average who will come out on top.

Summary

People play games of many different types. It is easy to view them simply as either random or skilled but this misses important distinctions. Adding volatility into the framework brings into focus the differences between say chess and poker, fundamentally different games and enjoyable in their own ways.