I am confused by the calm coverage of the recent radical shift in economic policy – described by the BBC as “bid to boost growth”. This type of reporting does not make clear whether we are talking short-term growth or long-term potential, and how these policies impact each of them in very different ways. From conversations with friends, much of the analysis does not investigate this and ultimately reveal just how dangerous and radical this new set of policies is.

Potential Output – what is it?

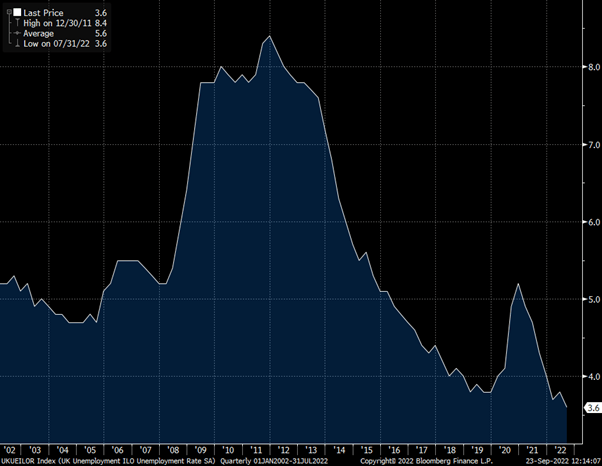

Truss has justified her policy changes economically citing improvements in the UK’s long-term growth potential i.e. increasing potential output

Potential output is the starting point for thinking about how much the country can produce ie it is the maximum sustainable level of output.

If we are below, then this is called a negative output gap and we see things like unemployment rates being high and inflation likely falling.

The OBR does a great job on this and their website is very clear

Potential Output – how can we improve it?

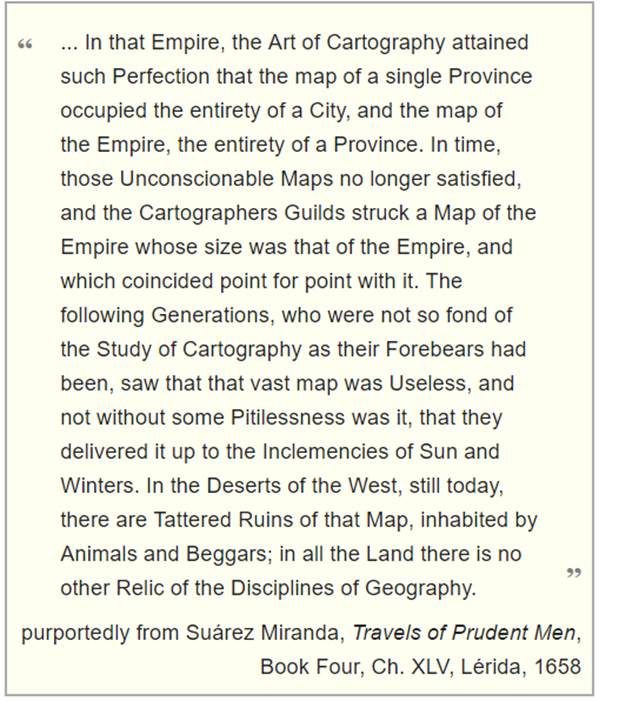

Everyone wants to improve potential output and there is a clear left vs right divide on how best to achieve it.

Truss is firmly in the right-wing supply-side movement of “trickle-down” i.e. give tax breaks to rich people and everyone will be better off because somehow this leads to greater potential output. Reagan was the most prominent exponent of this view but we are still waiting for any evidence that it works.

Potential Output – will it work?

I think best to simply summarise that there is no evidence that cutting taxes has any positive effect on potential output.

OK – so if Trussonomics does not improve potential output, what does it do?

It does a LOT

The most obvious and direct impact is of course on inequality. She is delivering a massive cash handout to rich people. The richer you are the more you get.

The part that is getting less attention is the impact on

- Fiscal vs interest rate policy mix

- Debt sustainability

- Fiscal vs interest rate policy mix

This policy choice has been perhaps at the heart of the political battle of the past decades and is commonly misunderstood. This is a shame as a simple quadrant model does a good job of providing a framework to compare the options clearly. (Fiscal policy is the mix of tax and spending with high spending/low tax being loose fiscal policy)

Tight fiscal -tight monetary When you are committed to fighting inflation above other policy goals. For example, the 1980s or commonly after an economic crisis when trying to rebuild confidence in the currency and debt. If used inappropriately looking at the 1930s Great Depression.

Tight fiscal – loose monetary This is the Cameron years. There is of course a debate over how tight fiscal policy should have been and on how the mix of tax and spending was managed. But it is a consistent policy mix

Loose fiscal – loose monetary This was at its maximum during the pandemic i.e. for a short term huge negative shock. If used long term it just leads to economic catastrophe.

Where are we now?

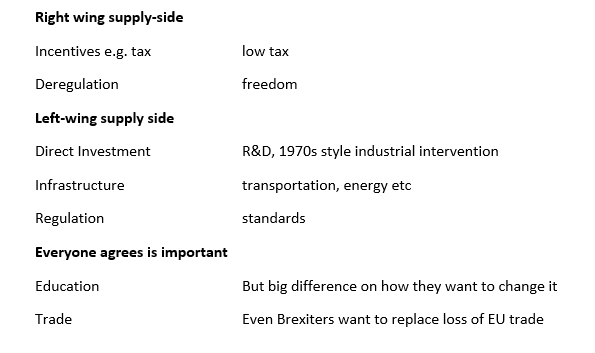

We are currently in the loose/loose box. Taking the unemployment rate as a simple measure of the output gap, you can see from the chart below we are at record lows. This is also clear to anyone trying to hire at the moment and all the reports of staff shortages. Which makes it odd that Truss talks about “boosting growth” as there is no prospect of lower unemployment from here.

UK Unemployment at record lows

The other factor that makes going for growth an odd policy goal is that inflation is high and rising. This does not have an easy solution and economic pain is unavoidable. Trying to avoid it, leads to even greater pain later.

UK Inflation at 30-year highs

What happens next?

The Bank of England will be forced to raise interest rates by huge amounts. At the start of this year the market expected interest rates to stay at around 1% though 2022 and 2023. Now the market expects rates to be 4% by the end of this year and 5.5% by the end of next year- with rate expectations for next year shifting 3% since the start of August.

What does this mean for people?

Well rich people have had a large tax cut and will be fine – I know you are all relieved to hear this.

Anyone on a regular income has had a small tax cut but this will be dwarfed by the rise in the mortgage payments coming soon.

What does it mean for the economy?

I predict a very bumpy path and hard landing for the economy but difficult to say when. The policy mix of vast fiscal expansion at a time of low unemployment and high inflation to be offset by rapid interest rate rises is a chaotic mix. I think the economy will stay strong and then crash hard.

- Debt sustainability

This is getting some attention but is being dismissed by Truss. The fact that they did not let the OBR produce a forecast tells us a lot about how they have contempt for this constraint on policy. An Office of Budget Responsibility is not what the Chancellor wants to hear from!

But the bond market still exists, and long-term government borrowing is getting hammered. 30-year Gilt yields have risen from under 1% at the start of the year to 4% as I write this.

The tax cuts and extra spending increases the budget deficit. The rise in interest rates increased the cost of servicing the debt, further increasing the budget deficit. This can become an exponentially explosive mix with the major accelerator being a currency crisis as the value of sterling falls.

Conclusion

The Trussonomics experiment is radical and dangerous. I expect high inflation, high interest rates and a weak currency leading to economic crisis. Politically I expect her to start to blame the Bank of England as though the rise in interest rates was not a direct result of her policies. The Bank of England may be independent of the government, but they are not independent of economic reality.

Truss has spoken of her disdain for “abacus economics” and she does not believe things need to add up. I think economic reality exists and her magical money tree fantasy will fail.